Researchers are calling for the conservation of teeny tiny organisms that normally get overlooked, and conservationists are listening.

With so many coral reefs bleaching and pangolins being poached, it may seem tone-deaf to call for the conservation of species that are too small to see with the naked eye. But that’s exactly what the world’s largest international conservation organization did last month.

On September 12, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) announced that they’ve put together a “Microbial Conservation Specialist Group,” a task force of scientists, conservationists, and volunteers whose mission is to safeguard our planet’s microbial biodiversity.

Microbes are so essential to maintaining life on earth, the commission’s members say, that trying to protect individual species or habitats without considering the microbes they rely on is a futile effort. “Without microbes, there can be no conservation,” says Raquel Peixoto, a microbiologist at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology and member of the new commission.

Microorganisms, an umbrella term for bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other tiny lifeforms, are lurking everywhere, from the deepest parts of the ocean to the surface of your skin. Scientists estimate there are somewhere between one trillion and 100 trillion species. While there are plenty of microbes that we could live without, such as the virus that causes COVID-19 and the fungus responsible for athlete’s foot, there are an unfathomable number that we couldn’t.

Microscopic algae and cyanobacteria produce more oxygen than all the plants on land. Bacteria and microscopic fungi enrich soil, turning nitrogen into a form that helps plants grow, and breaking down organic matter. At any given time, there are around 30 trillion microbial cells in your body, supporting everything from your immune system to your mental health. It would not be overdramatic to say that microorganisms are necessary for all life on Earth.

(Trillions of microbes affect every stage of your life.)

Studies show that industrialization, habitat loss, climate change, antibiotic overuse, and pollution are causing our planet’s microbial diversity to decline at an unprecedented rate. It’s also clear that this decline is negatively impacting the health of humans, animals, and the ecosystems we depend on for survival. So, what should be done about it?

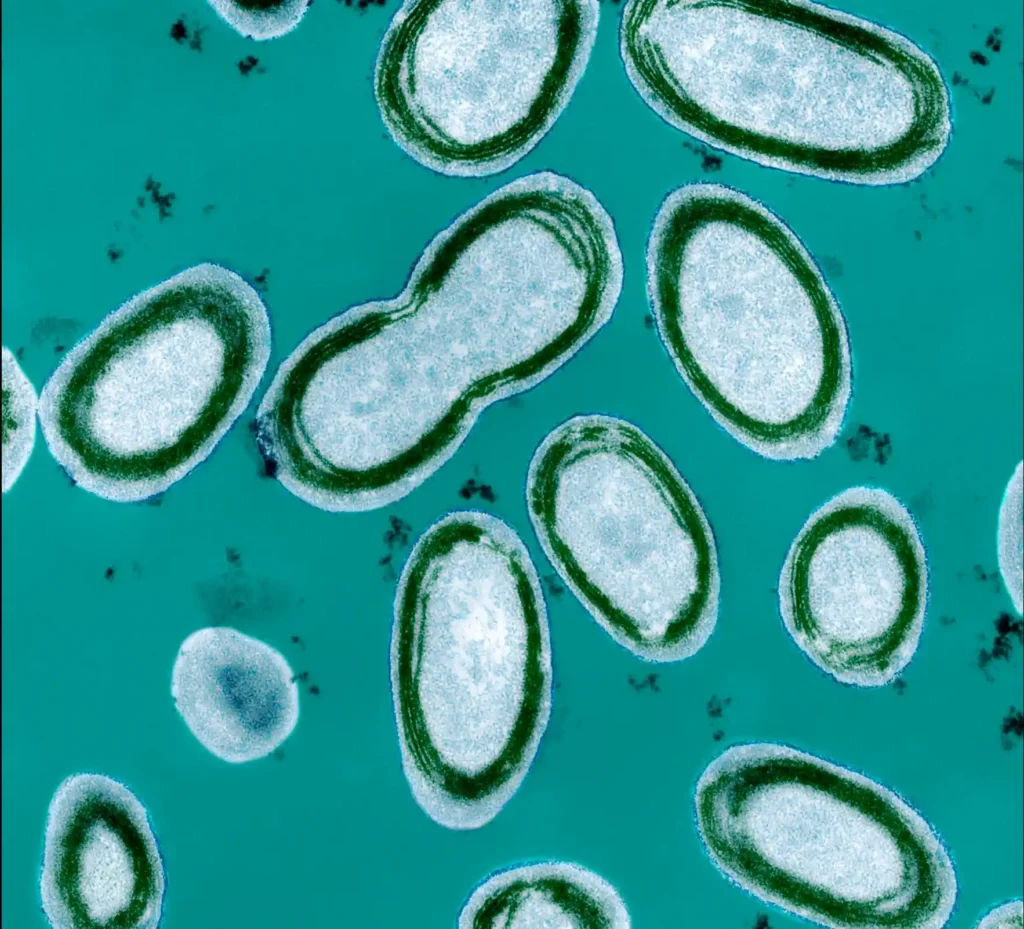

Single-celled cyanobacteria called Prochlorococcus live in the open ocean and play an important role in regulating levels of carbon dioxide and oxygen in the atmosphere.

MICROGRAPH BY CLAIRE TING, SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

In a paper recently published in the journal Nature Microbiology, Peixoto and her fellow commission members offer practical ways to do this, including the creation of microbial bio banks (think the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, but for microbes), the protection of natural microbial habitats, and the development of probiotic boosters for imperiled humans, animals, and ecosystems.

Calls for microbe protection have historically been few and far between. “Microbes are the foundation of ecosystems yet remain largely overlooked in conservation efforts due to technical limitations, limitations in understanding the complexity of their structure and function, and bias in favor of things one can see,” said Elinne Becket, a microbiologist at California State University, San Marcos, who is not a member of the new commission.

Because of this, convincing traditional conservationists to consider the microbes when making conservation decisions has long been difficult, says Jack Gilbert, a microbial ecologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and a member of the new commission. Though some were initially skeptical this time around, he says many conservationists are now voicing their support for the new commission because its work will ultimately help them protect coral reefs, pangolins, and more.

Here are five examples of microbes that the group thinks are worth saving—the threats they face and the ecosystems that could collapse without them.

PROCHLOROCOCCUS PROTECTS THE OPEN OCEAN

Out in the open ocean, trillions of bacteria known as Prochlorococcus are sucking up carbon dioxide, producing oxygen, and fueling the open-ocean food webs that everything from blue whales to bluefin tuna depend on. Prochlorococcus are sensitive to ocean warming, acidification, and nutrient shifts, so if climate change continues to march along unimpeded, Gilbert says, these essential bacteria and the ecosystems they support could be in serious jeopardy.

These Acropora corals off Caroline Island in the Pacific Ocean have bounced back after a 2015-2016 warming event killed most of them. Maintaining populations of Beneficial Microorganisms for Corals (BMCs) is vital for coral health.

PHOTOGRAPH BY ENRIC SALA, NAT GEO IMAGE COLLECTION

CORAL REEFS NEED TWO TYPES OF MICROBES TO SURVIVE

From the shallows to the edge of the twilight zone, coral reefs rely on symbiotic microorganisms to sustain themselves. The microorganisms that enable their survival are Symbiodiniaceae, known colloquially as zooxanthellae. These microscopic algae provide corals with the essential energy they produce during photosynthesis in exchange for a safe place to stay. Another special group of microbes referred to as Beneficial Microorganisms for Corals (BMCs) fight pathogens, help corals absorb nutrients, and degrade compounds that are toxic to corals.

Rising ocean temperatures, pollution, and diseases can cause corals to expel the symbiotic microorganisms from their bodies, a phenomenon called coral bleaching. Probiotic boosters administered before or during a heat wave could lessen the severity of these die-offs.

Without these microorganisms, the coral reefs we know and love would be white, lifeless piles of rock. At least 25 percent of ocean life depends on coral reefs for survival. Reefs also help protect our coastlines from storms and provide nursery habitat for the fish we eat.

MICROCOLEUS VAGINATUS BUILDS DESERTS AND GRASSLANDS

Our planet’s deserts and grasslands are being held together by a group of bacteria known as Microcoleus vaginatus—literally. While the name may sound like a venereal disease, it’s actually a cyanobacterium that helps keep soils in dry environments from desiccating and being swept away by wind and rain.

Given that such environments cover around 40 percent of Earth’s land surface, these bacteria are the only thing standing between us and colossal dust storms and widespread desertification. While Microcoleus vaginatus remains one of the most abundant terrestrial cyanobacteria on earth, they are under threat from industrial agriculture and drought.

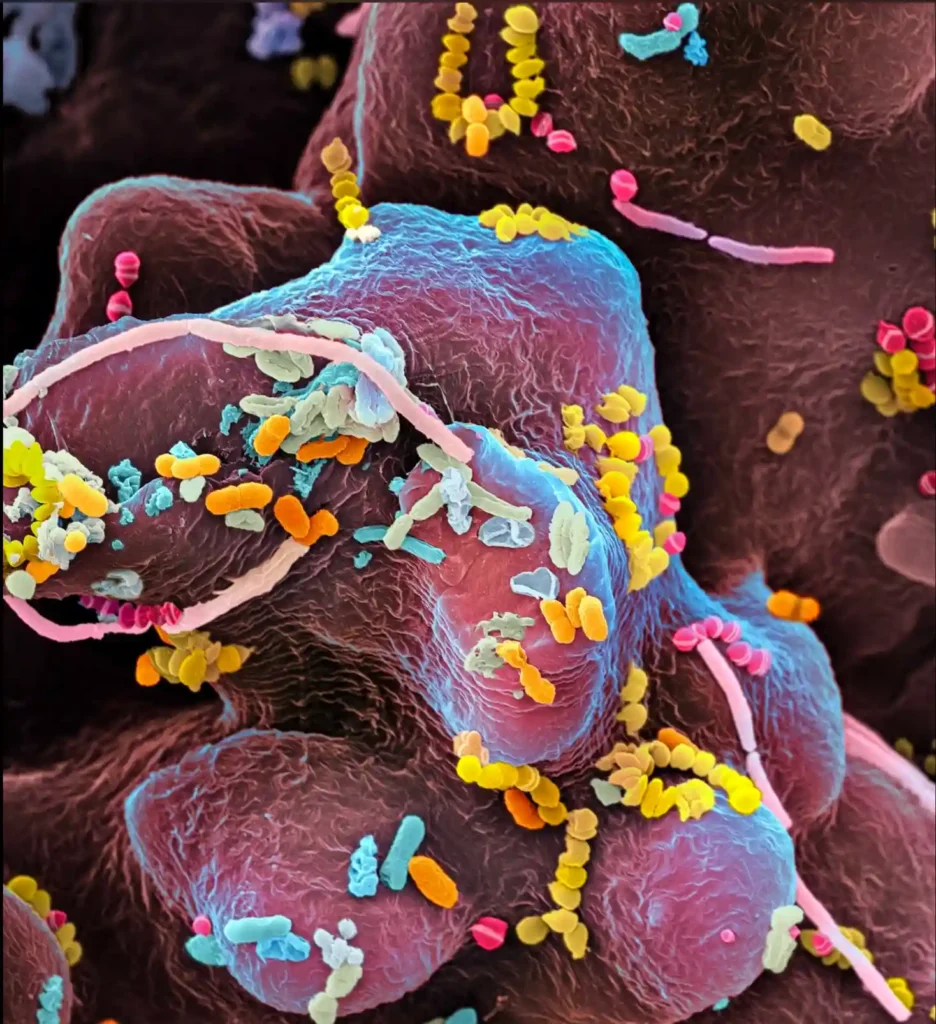

The human body contains trillions of microbial cells. More than 600 identified species make up the oral microbiome alone and probably many more remain still unnamed.

MICROGRAPH BY MARTIN OEGGERLI, NAT GEO IMAGE COLLECTION

A HOST OF MICROBES SUSTAIN THE HUMAN BODY

Our bodies contain a plethora of microorganisms that we’ve been evolving alongside for millions of years. The ones in our digestive tract help us break down complex fibers, maintain the layer of mucus that protects our stomachs from acid and digestive enzymes, synthesize and absorb many vitamins, and so much more.

Unfortunately, our ultra-processed, low-fiber diets, overuse of antibiotics, and reduced exposure to natural environments have decreased the diversity of our gut microbiome. This loss of diversity has been linked to higher risks of inflammatory and autoimmune disease, allergies, obesity, and type 2 diabetes.

ACTINOMYCETES FILL OUR MEDICINE CABINETS

A group of bacteria known as actinomycetes have given us some of the most important medications in human history. These bacteria are used to make antibiotics and immunosuppressant drugs, as well as industrial enzymes. But outside of the lab, actinomycetes also keep soil healthy by decomposing chitin and other tough-to-break-down molecules, cycling nutrients, fixing nitrogen, and defending plants against pathogens. They also give healthy soils their characteristic “earthy” aroma.

(Meet the marvelous creatures that bring soil to life.)

Intensive agriculture, land degradation, pollution, and climate stress threaten actinomycetes, which humanity needs for both farming and the development of new antibiotics. Conserving land that hasn’t been impacted by human activity and curated actinomycete collections in labs, Gilbert says, is of the utmost importance.

Original Link